In Dostoevsky’s novella “The Double,” a low-level bureaucrat’s life is turned upside down when he meets his doppelgänger on the streets of St. Petersburg in a blizzard. What begins as a friendly encounter soon turns dystopian as the imposter slowly takes over Golyadkin’s life, sending him deeper and deeper into madness.

The theme of the doppelgänger (literally “double goer” in German) is a classic mythological and literary trope appearing in many world traditions. Ancient Egyptians believed in the ka, or “spirit double” — a non-physical entity that shared the thoughts and desires of its human counterpart. Hopi Native American legend has it that good people living in the conscious realm of the Upper World are mirrored by their evil doubles in the Under World. From the works of Edgar Allen Poe to Robert Louis Stevenson, European and American Gothic literature abounds with the figure of the doppelgänger as a mechanism to explore the shadow side of human psychology. The idea of an evil force subsuming its human prey taps deep into the collective unconscious and raises the primordial fear of losing one’s sense of personhood and grasp on reality. The double appears as a mirage rising out of the uncanny valley — one is never certain of its orientation or its intentions, and is left with a lingering, eerie feeling of unease.

Double Vision

With the advent of artificial intelligence, the life of the doppelgänger has taken on a new form in recent years. What was once the province of allegory and myth has become science fiction reality: the digital twin. According to the National Academy of Sciences:

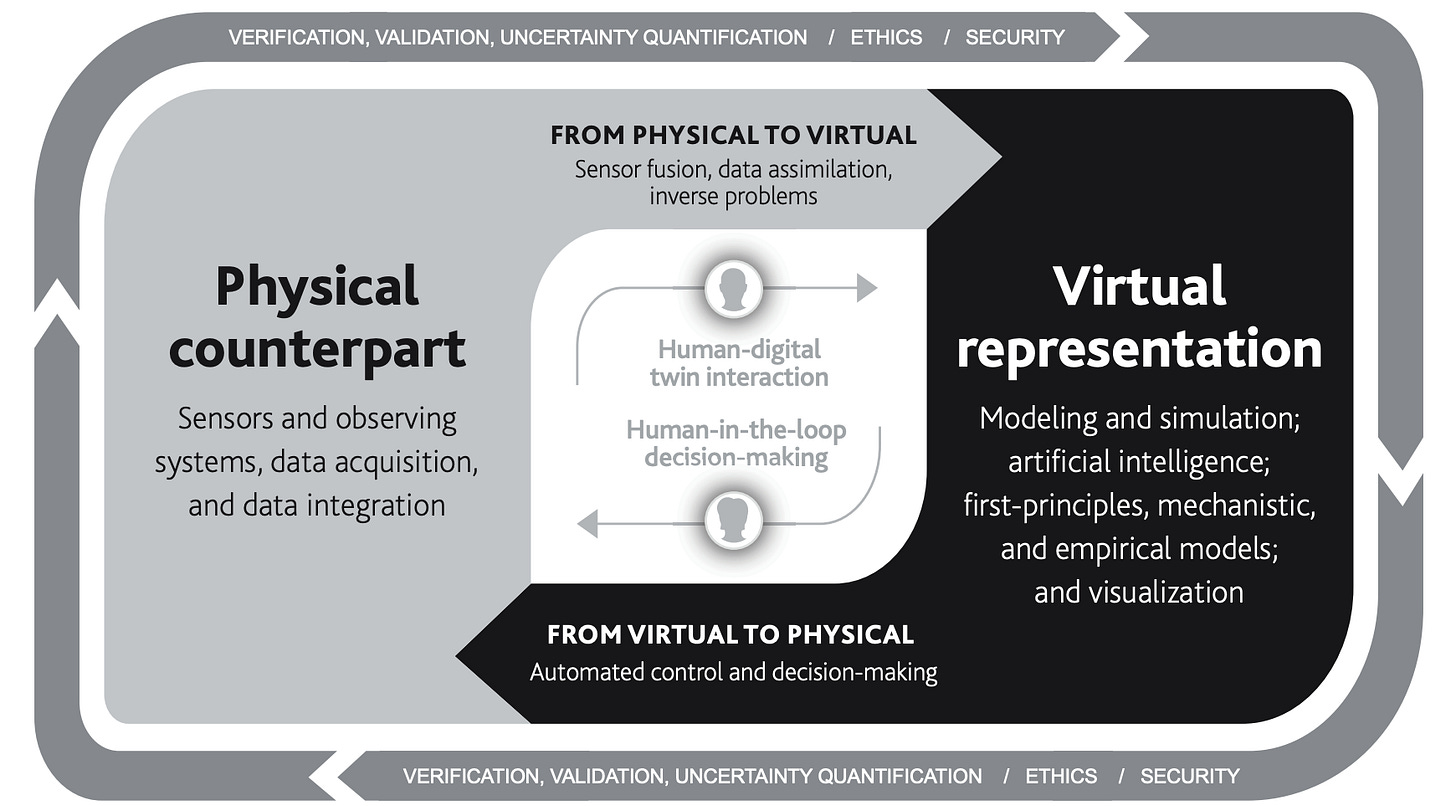

A digital twin is a set of virtual information constructs that mimics the structure, context, and behavior of a natural, engineered, or social system (or system of-systems), is dynamically updated with data from its physical twin, has a predictive capability, and informs decisions that realize value. The bidirectional interaction between the virtual and the physical is central to the digital twin.

The diagram below illustrates the components and feedback loops of a typical digital twin system. The interactions show how information picked up from the physical world via sensors is converted to a digital representation of the real world for the purpose of modeling, simulating, and visualizing various inputs. The results of these models and simulations for system improvement and maintenance can then be translated back into the real world through automatic or manual (human-in-the-loop) adjustments.

The first use cases for digital twins were relatively confined to the aerospace industry as tools for aircraft preventative maintenance and non-destructive materials testing and analysis. As the technology became more sophisticated and as other industries continued to digitize their workflows, new opportunities for digital twins emerged. Today, digital twin applications are proliferate across healthcare, weather and climate modeling, ecosystem management, manufacturing, and energy generation, transmission and distribution systems. Indeed, the worldwide digital twin market is expected to reach $155.84 billion by 2030, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 35.7%.

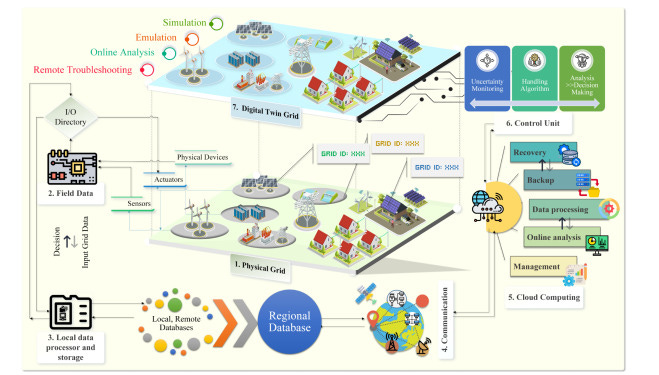

In the energy sector, digital twins offer hope to solve some of the most pressing problems facing the modern grid system. U.S. grid infrastructure, dating mostly from the 1960s and 1970s, is rapidly aging and is in dire need of upgrades. Additional pressure as a result of integrating utility scale renewables, microgrids, and home distributed energy resources (DERs) into the grid system requires an expansion of transmission towers and lines. According to a recent report by BloombergNEF, the global push towards net zero will cost $21 trillion in power grid investments.

Through building digital twins of grid infrastructure, both at the level of individual assets, and as a model of the networked system, utilities and grid operators can assess and predict problems in real time, leading to greater system-wide efficiency and optimization. In the ideal digital twin system, a so-called “digital thread” allows the operator to amalgamate all plant processes into a single database (e.g., GIS, equipment operation and maintenance, and SCADA data) and feed it into an AI-supported analytics program to make sense of the individual datapoints on a holistic level. This sense-making process provides concrete, actionable messages regarding the overall health of the plant, and can troubleshoot and triage problem areas. With the increased complexity of disparate renewables assets on the grid, digital twins can also centralize distributed resource management and inform operators how to prioritize these resources in a fashion that is most economical, energy efficient, and reliable. Better stewardship of existing infrastructure can furthermore help extend the useful lifetime of older transmission units. In short, digital twins give energy system managers the power to become proactive rather than reactive to equipment and transmission issues that threaten grid reliability.

The Evil Twin

While the promise of digital twins in energy systems is potentially great, significant challenges remain. One major hurdle to realizing a fully digitized “smart grid” is the reliance on huge amounts of data and AI training algorithms inherent in any “smart” system. Somewhat paradoxically, the very resource that may increase grid efficiency (actionable data analysis) also adds strain on the grid as a whole, as the back-end data processing centers and storage units are energy hogs, and are set to consume nearly 10% of total U.S. electricity generation by 2030. Moreover, digitizing a grid system designed for the analog era is difficult, as the equipment may not be compatible with more advanced sensing technologies, and may result in data collection gaps and inconsistencies that pollute the integrity of the system as a whole. Transmission assets in areas with poor internet connectivity may also suffer from data latency, leaving the infrastructure vulnerable to performance problems that go undetected.

Another serious concern is the cybersecurity risk associated with managing digital assets. Any unsecured data access point on the grid could provide entry to hackers, who then may disable key infrastructure, leading to localized or even widespread blackouts. Unauthorized access to a plant’s central dashboard may allow a nefarious agent to manipulate data inputs, which could cause the energy management system to function erratically. Similar events have already occurred. For example, in 2006, the Brown Ferry nuclear facility in Alabama shut down when a cyberattack flooded the control network with excessive traffic and overwhelmed the system. As the energy grid becomes more digitized and regional assets are integrated into a single, streamlined system, the potential risk of cyberattack grows exponentially and data manipulation attacks could trigger a domino effect taking out large swaths of the grid.

At the individual level, residential prosumers (producer-consumers) of solar DERs providing energy and information to the local utility could come under DDoS and other malware attacks, allowing cyberhackers to access, disable and destroy any digital device connected to the home wi-fi network (e.g, smart hubs, smart appliances, personal electronics). These kinds of attacks further leave utility customers vulnerable to improper surveillance and identity theft.

As experts have warned repeatedly, our ability to protect essential grid services and mitigate security risks is currently inadequate. To advance the smart grid without commensurate investment in securing grid infrastructure would be to put the cart before the horse, with potentially catastrophic results.

Finally, the current lack of standardized and interoperable protocols governing the smart grid system represents a roadblock preventing system-wide optimization. The International Electrotechnical Commission established a technical committee in 2022 with the aim of designing codes and standards for the express purpose of laying a coherent regulatory foundation for the smart grid and digital twins. These protocols fall under IEC 61850 and IEC 61970, which deal with communication networks for utility automation and energy management interface systems, respectively. An additional working group (SC 41) on the Internet of Things (IoT) and digital twins was developed as a joint effort between IEC and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) to tackle the difficult problem of creating seamless inter-device communications and a vertically integrated digital twin ecosystem. While some progress in this area has been made, it is not yet clear when or if smart grid interoperability protocols will be realized. Chief among many challenges is the propriety nature of energy management systems, which are fiercely protected under patent by their respective manufacturers. Main players in this space include GE, Siemens, and Schneider Electric.

The Robot Becomes Us

In the U.S., the current state of the smart grid and digital twin technology provides some fault detection and automatic control, but stops short of being fully integrated into an intelligent system using AI and machine learning to optimize energy grid operations. Some utilities, such as San Diego Gas & Electric (SDG&E), use simple AI systems to monitor infrastructure and identify preventative maintenance issues before they affect power distribution and transmission. Many California utilities now regularly synthesize geospatial and weather data into their grid management systems to identify wildfire risks, and may target localized sections of the grid for Public Safety Power Shutoffs (PSPS) to prevent power lines from sparking fires in vulnerable areas.

In our brave new world of AI, the uncanny valley is increasingly all around us. From deepfakes, to hyper-realistic computer-generated artwork, to algorithm hallucinations, the digital landscape has opened up a chasm of uncharted territory, where the boundaries of our real identities and our double lives online become blurred. The digital twin, whether as a map of the energy grid, or a robot copycat of an industrial plant worker, is just the logical continuation of this slide into a fully merged metaverse. Whether that digital twin will be more Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde remains to be seen.

Electrically yours,

K.T.

Very interesting energy especially in terms of security, espionage , and hackers.

Great job.

Another home run!