The Good

We’ve come a long way since the days of the washboard. And good riddance. Household appliances make modern life possible, freeing us (and women in particular) from toil and drudgery. With the evolution of white goods over the decades have come new innovations to improve performance and customer satisfaction. I mean, who doesn’t love a washing machine that sings Schubert to you when it’s done? But novelties aside, what drives industry to serve up the products they do? A lot of it has to do with the Department of Energy’s rules and regulations on appliance efficiency standards. And 2024 is shaping up to be a hot year in the home goods regulatory cycle, leading to policy that will determine product design for decades to come.

In September 2023, the White House announced a proposed agreement on new efficiency standards for a variety of household appliances, including refrigerators and freezers, wine and beverage chillers, clothes washers and dryers, dishwashers and cooking products. The new rules were touted as as a successful collaboration between government and industry, endorsed by the Association of Home Appliance Manufacturers (AHAM) and a coalition of NGOs such as the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE), the Appliance Standards Awareness Project, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), and others. Currently winding their way through the bureaucratic labyrinth, the preliminary standards are set to be approved by the DOE in mid-2024, and go into effect over the next three to six years.

Originally established as a result of the 1970s oil crisis, the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA) grants the DOE authority to implement minimum energy efficiency standards for 50+ products in residential and commercial applications, with review requirements every six years. The motivating factor behind stricter energy efficiency standards seems innocuous enough: an attempt to save consumers energy and money on their utility bills, and reduce overall greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Indeed, the DOE stated in a press release in December that the new regulations are projected to generate around $1 trillion savings in avoided energy costs over 30 years, and reduce GHGs by 2.5 billion metric tons.

The Bad

An emerging theme of the energy policies discussed in The Joule Thief may be summed up as “all that glitters is not gold.” And so it may be the case with the Biden Administration’s proposed appliance amendments. Efficiency in energy and water usage often comes at the cost of expediency and thoroughness. As an instructive example, consumers complained in response to the 2018 code cycle’s restrictions on water usage in residential clothes washers, flooding online reviews with comments about clothes not getting sufficiently clean. Some said they had to stop the machine mid-cycle to add more water manually. Furthermore, because efficiency standards broadly favor front-loading washers over top loading models, the increased market share of these products bring new challenges. For example, customers must perform regular maintenance to prevent mold from growing inside the rubber gasket that encapsulates the internal cylinder. Similarly, poor performance of dishwashers with increasingly stringent water usage leads customers to pre-rinse or run the machine twice, threatening to cancel out any efficiency that might have been achieved otherwise. Even worse, decreased power draw has resulted in dishwasher cycle times climbing to about 160 minutes on average, up from only 60 minutes forty years ago:

Adding to the woes of longer run times and questionable cleanliness, appliance efficiency standards are increasingly abutting another limit: the laws of physics. As Kevin Messner, chief policy office of AHAM, stated during a congressional hearing in 2023, “The reality of the laws of physics require some amount of energy and water for home appliances to keep cold and to clean and dry clothes and dishes has to be recognized.” In a recent statement to the Wall Street Journal, Pamela Klyn, chief sustainability officer at Whirlpool, admitted that appliances are nearing their limits to efficiency. She comically added that reducing the energy consumption of a microwave “would mean removing its clock.”

The Ugly Policy Battle Ahead

Further tightening the screws on appliance efficiency standards looks increasingly untenable. So what’s a regulatory hammer in want of a nail to do? Returning to scientifically-backed analysis may be a good place to start. Several years ago, the DOE commissioned a study from the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), asking experts in energy efficiency policy to review the appliance standards regulatory process. The report, “Review of Methods Used by the U.S. Department of Energy in Setting Appliance and Equipment Standards,” was published in 2021. The committee recognized shortcomings in the current code-making methodology, particularly noting its inability to understand and forecast social and economic externalities associated with the new measures. This means, rather than focusing solely on engineering models of reduced energy or water usage, the DOE should assess technological feasibility and economic impact, involving the evaluation of “whether the benefits of the standard exceed its burden.”

The report recommends the adoption of a framework based on “Regulatory Impact Analysis” (RIA). In short, RIA presents a way to account for social welfare aspects of regulation, including identifying the consequences of regulatory alternatives, evaluating qualitative non-energy costs and benefits, and characterizing uncertainty and incongruities between adoption and benefits accruing to different demographic groups. For example, such a framework would be better equipped to model whether the increased cost of more efficient products are merited and can reasonably achieve commensurate energy savings. If not, higher costs may put undue burdens on the consumer, particularly in low income and disadvantaged communities.

As Susan E. Dudley, director of George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center and contributor to the NAS study wrote for Forbes:

One-size-fits-all energy efficiency standards that ignore variation in household size, income, and geographic conditions prevent consumers from making purchases that fit their circumstances and constraints. The Subcommittee and DOE should recognize that preventing consumers from purchasing appliances that meet their diverse needs is not a win-win; it is a cost that especially hurts low-income consumers.

Moreover, the review emphasizes the need to rigorously compare expected outcomes with ex-post ante data as part of a formal, iterative rule-making process (ex-post ante data is collected after the policy has been put into place, showing whether the projected impacts actually happened in reality, thus shedding light on its effectiveness). Requiring the DOE to hold a mirror up to its promised deliverables improves governmental transparency and accountability.

Finally, the NAS report stresses the need to future-proof regulatory environments for advanced technologies. While individual, device level engineering impacts may have sufficed in the past, technology is increasingly trending towards holistic, household level energy consumption patterns, enabled by the Internet of Things and “smart” and connected devices: Alexa speakers, Nest thermostats, etc. This “integrated grid” thus calls for a new way of approaching regulation that accounts for coherent ecosystem efficiency, rather than bean-counting every single washer or dryer.

The findings of the NAS seem like reasonable improvements to me. But, of course, in its infinite wisdom, the DOE has chosen to pursue business as usual. While the final rule-making procedure is still underway, none of the publicly available developments suggest that the DOE has taken seriously the NAS’s recommendations for a fairer, more effective energy efficiency regulatory paradigm.

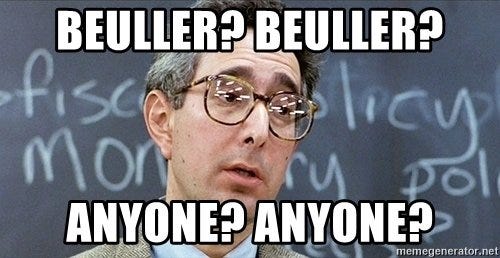

So I’ll leave you with this final question: what’s the point of soliciting expert opinion, if you’re not going to listen to it? Anyone?

Electrically yours,

K.T.

*Addendum: Just hours after this piece was published on Feb. 29, 2024, the DOE released its proposed decisions on residential washers and dryers. The clothes washer decision report included this delicious nugget:

AHAM stated that despite previous requests from AHAM and others, DOE has failed to review and incorporate the recommendations of the NAS report…AHAM further stated that DOE seems to be ignoring the recommendations of the NAS report and even conducting analysis that is opposite to the recommendations.

Q.E.D.

Title says it all, clever!