Oh, the holidays. A time for gathering with family and friends, eating too much…of everything….and binging on cheap “discount” goods from the likes of Amazon, Chinese retail giant Temu, and other purveyors of alluring Black Friday deals. In our tech-obsessed world, electronics products and appliances top the list for many would-be bargain hunters. To wit, a cursory search for “Black Friday” and “Electronics” returns thousands upon thousands of hits on Amazon’s website, ranging from electric can openers to top-of-the-line QLED TVs, and everything imaginable in between. Ostensibly, shoppers are hoping to spend and spread joy to those near and dear. Aunt Betty will love her new toaster oven. But, what inevitably happens when that toaster oven is no longer functional, or capable of sparking joy? Enter the nebulous, nefarious world of electronic waste (“e-waste”) recycling.

A Circuit Board Jungle

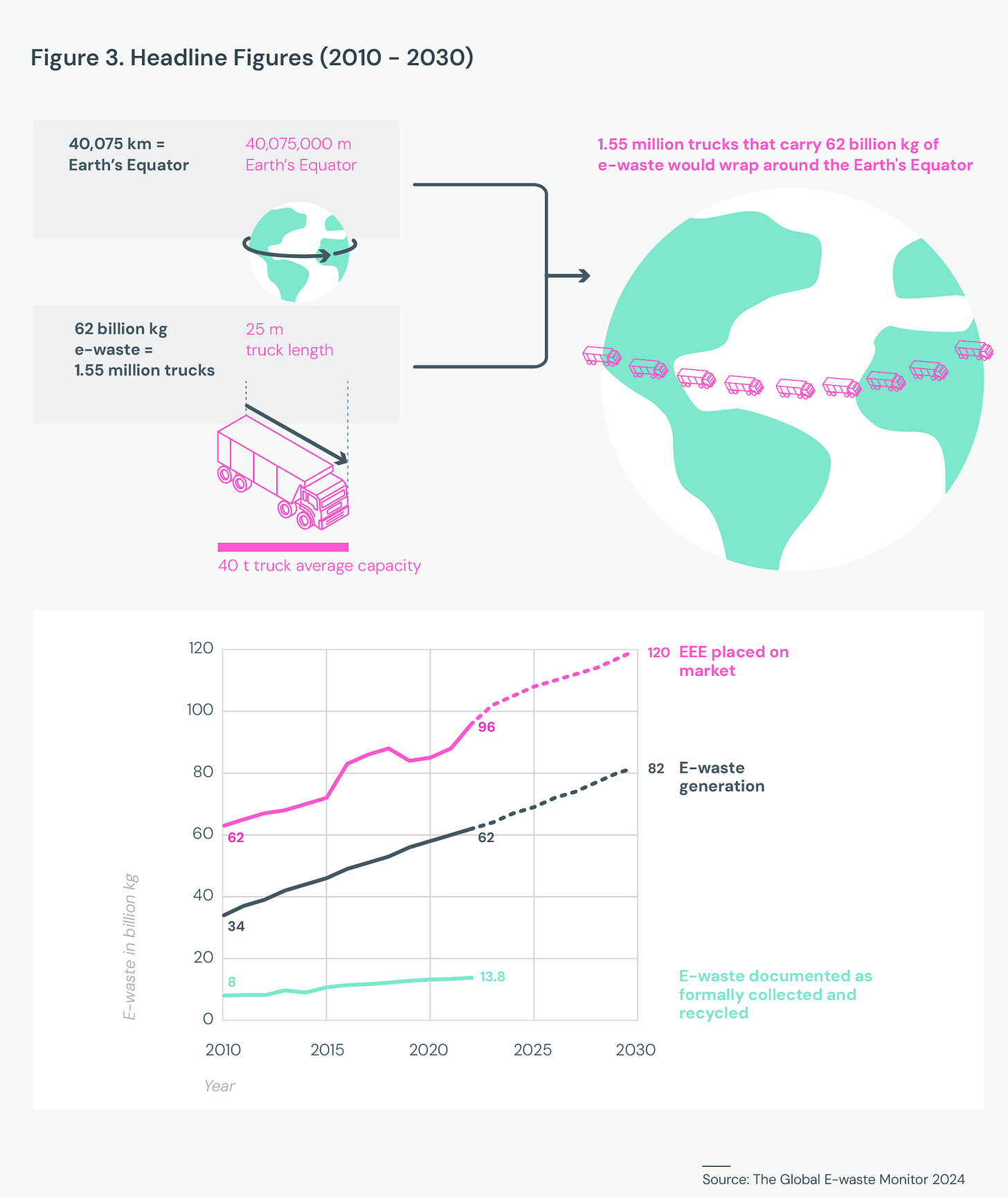

According to the United Nations Global E-Waste Monitor 2024, 62 million tons of e-waste was produced globally in 2022, up 82% compared to 2010 — enough waste to fill 1.55 million 40-ton trucks, and that would roughly stretch bumper-to-bumper around the circumference of the earth. By 2032, this figure is set to rise another 32%, reaching a whopping 82 million tons annually. What’s more, recycling rates for these products is abysmal. Even in the heavily regulated European Union, only 42% of e-waste was documented as properly recycled in 2022, and these recycling certificates do not guarantee that the products have not been illegally shipped and dumped in foreign countries after initial processing.

Recent investigations, such as the hit Netflix documentary “Buy Now!” (released just in time for Thanksgiving 2024), and studies by the United Nations Environment Programme have brought to light the proliferating black market of transnational e-waste commerce, a practice that is nominally illegal in the E.U. and parts of the U.S., including many states with large urban centers, such as California, Illinois and New York. Sting operations have revealed licensed recycling facilities and manufacturers in rich countries selling and shipping unwanted, damaged electronic goods by the millions to poorer nations where environmental protection regulations are lax, or missing altogether. Popular destinations include Southeast Asia, such as Hong Kong and Thailand, and West Africa, such as Ghana and Nigeria.

Once arrived via cargo container ships, computers and monitors, smartphones, TVs, stereos, and a myriad of plug-in appliances are sent to scrap metal facilities, where workers strip valuable components out of the products, usually without appropriate hazmat gear to prevent exposure to heavy metals via air and skin contact. Inadequate control of toxic waste streams also pollutes the surrounding environment, where high concentrations of elements like mercury and lead, as well as plastics and chemical effluents end up flowing into residential neighborhoods, lakes, rivers, and eventually, out to sea. By now, nearly everyone is aware of the dangers that mercury and microplastics pose in contaminating the ocean food-chains and damaging human health.

Recycling ABCs

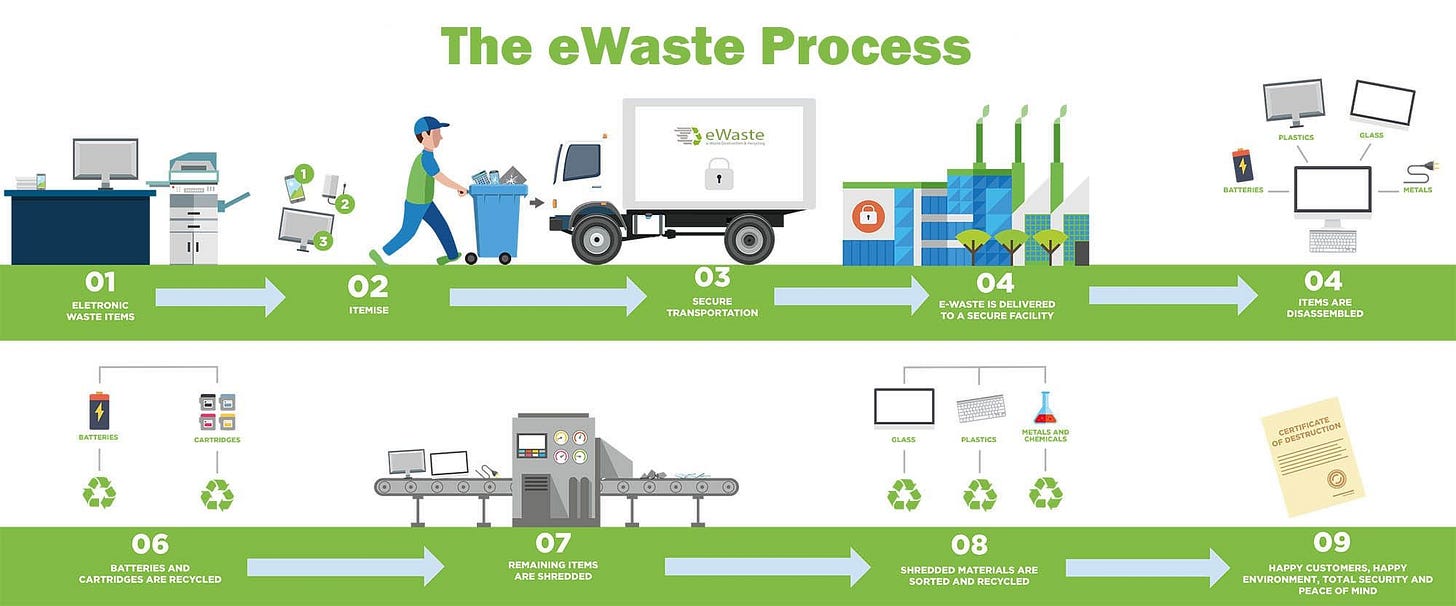

So what does e-waste recycling look like, when done properly? When old electronics first arrive at the plant, they are sorted by device type and examined to determine whether some parts are still functional - these are salvaged and sold either individually as refurbished replacement pieces, or combined to make a new product made of recycled components. However, the vast majority of recycled electronics are not salvageable, and are then sent to further processing.

Next, the e-waste goes through the de-manufacturing process, “which refers to the action of disassembling a product into components. This procedure is to remove all the potentially hazardous materials in electronic devices that will destroy the machine or contaminate the environment once disposed into landfills.” After these dangerous materials are removed, the devices are shredded by machine and further sorted into various material types using magnetic currents to separate metals from plastics, and separate between metals and alloys (e.g., ferromagnetic vs. weak magnetic attraction). The metals left over, such as aluminum, copper, silver, and gold can then be collected and sold for market value.

While e-waste recycling is critical to reducing toxic waste and should be encouraged where possible, significant challenges lie ahead for the industry. The consumption treadmill encouraged by manufacturer-imposed “planned obsolescence,” combined with the policy push in developed nations towards “smart” appliances (i.e, refrigerators, washing machines, stoves, etc., with advanced onboard computer processing and internet connectivity capabilities), will only exacerbate the problems highlighted here. Indeed, experts in the field expect the gap between e-waste produced and e-waste recycled to widen within the next five years. In an interview with CNN, Vanessa Gray, an advisor to the International Telecommunication Union and contributor to the U.N. E-Waste Monitor Report, stated that “the recycling rate could actually drop over the next few years,” due to the fact that waste production is simply outpacing recycling processing capacity by orders of magnitude. Overall, the U.N. report anticipates that global e-waste recycling will decrease from 22.3% at present to only 20% by 2030.

Moreover, the increase of ever-more sophisticated integrated circuits and microchips make the challenge of recycling even more complex, as the technology for separating these tiny chips into component elements is immature. Similarly, rare earth minerals, though valuable, are not usually recycled due to the energy and chemical intensive methodology currently employed to strip them from solar panels, lighting, and personal electronics. Most of these materials will end up buried in landfills.

The Way Forward

The main pathway many national and state governments are taking to address the increasingly impossible to ignore problem of e-waste is regulation. The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, an international treaty for the safe and ethical disposal of electronics and other toxic waste, has been in place since the 1990s, with 191 countries currently as signatories. The treaty has been periodically amended with stricter requirements for e-waste management, including prohibitions on exporting products internationally. Although the U.S. is one of few nations that have not ratified Basel, 25 states and the District of Columbia have passed state laws that adhere to the treaty’s main tenets.

In addition to anti-dumping laws, codes and standards around consumer rights can be a promising method to lengthen the useful life of various products, thereby reducing the quantity of e-waste produced each year. In April 2024, the European Parliament passed the “right to repair” directive, which requires manufacturers to extend existing electronics and appliance warranties by one year, and prohibits product makers and distributors from refusing to repair older devices with expired warranties. The directive also allows independent repair shops to supply users with new and salvaged replacement parts. In the U.S., states such as California, New York, and Minnesota have “right to repair” laws on the books, and consumer protection advocacy organizations, such as Ifixit.org are raising awareness of e-waste overabundance and helping people learn to repair their own products at home.

However, legislation is only as effective as its compliance and enforcement, and, as the example of European countries dumping waste abroad demonstrates, there are glaring loopholes and powerful industries that compel would-be enforcers to look the other way. Furthermore, many companies may in fact find it cheaper to pay the fines levied for improper e-waste disposal than to comply with state and federal law. For example, in 2019, Target was fined $7.4 million in California for throwing e-waste in the trash — a figure that may seem high, but for a giant corporation, probably pales in comparison to the $4.00-$6.00 per item that the state’s recycling program currently charges.

The newest trend in the e-waste regulatory field is based on “lifecycle analysis,” which would purportedly require businesses to design and manufacture their products with end-of-life in mind. This may include replacing plastics with biodegradable materials, and designing chip components that can be more easily disassembled. But, as in all things “green,” seeing is believing. And all I see is a man behind the curtain, telling you not to believe your lying eyes.

As usual, the real answer comes down to physical reality. On a finite planet, with finite resources, the best we can do is consume less, and care for the things we already have. The old adage “quality over quantity” comes to mind.

“Buy now,” you say? I say “Bah Humbug!”

Electrically yours,

K.T.

Wonderful work!

During the depression, this saying became popular:

"Use it up, wear it out - make it do, or do without."

That was the exact opposite of a throw-away society.